On a foggy early January day in the northern Italian city of Brescia, which was hit hard by the first wave of Covid-19 in 2020, Stefania Triva, 57, sets out two swabs side by side on her desk. One is a regular cotton Q-tip, the other a special “flocked” swab, studded with tiny synthetic fibers that resemble split ends.

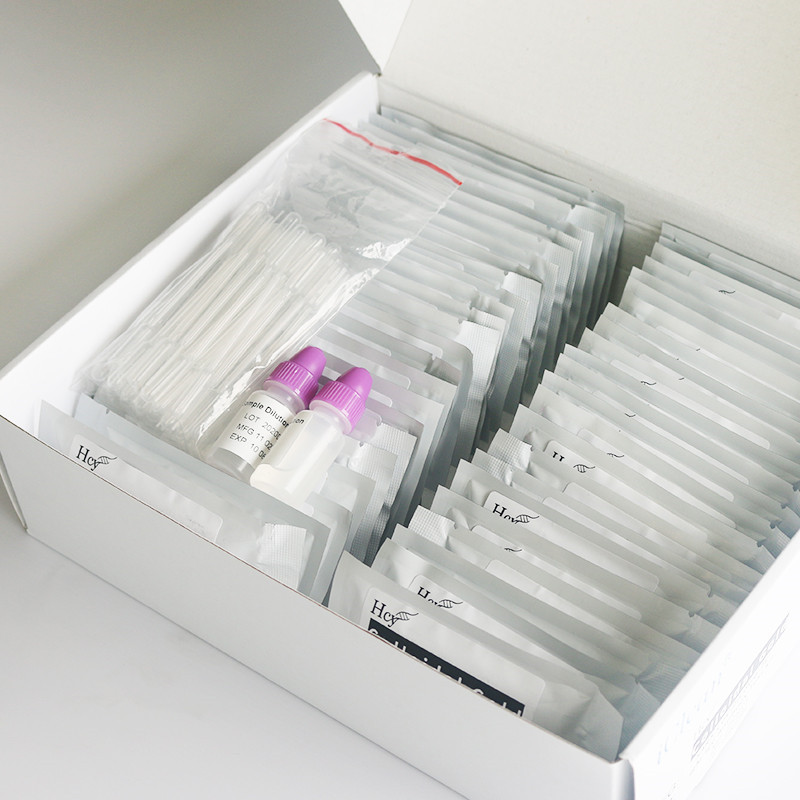

That special swab—made by her family’s 43-year-old company, Copan—is the key element in hundreds of millions of Covid-19 PCR tests currently being plunged into noses around the world. Sitting in front of a large red-and-yellow abstract painting and a corkboard filled with photos of her three children, Triva delves into the subtle differences that make her flocked swabs the gold standard. Sterile Swab Sticks

“In a cotton swab, the fibers are twisted around the stick, creating a cage that traps the sample,” she says, pointing to the thickly wound Q-tip. “But it only releases 20% of that sample. In a flocked swab, thanks to the mechanics of how the fibers are attached to the stick, you have the opposite: 80% is released.”

Those swabs—invented by Copan in 2003 and the subject of ongoing litigation with its leading rival, Maine-based Puritan Medical Products—have helped drive the company’s enormous growth; it manufactured 415 million of them in 2020, more than double the 2019 amount.

After ramping up production, Copan now has the capacity to produce 1 billion a year. Net income nearly quintupled in 2020, to $79 million, on revenue of $372 million. It blew past that figure in 2021, with sales growing to $445 million. (Net income was not yet available at press time.) A full 84% of Copan’s sales come from flocked swabs, which have been used in at least a billion molecular tests conducted in doctor’s offices and clinics around the world since the beginning of the pandemic. (That figure doesn’t include swabs for rapid tests or at-home kits, a tiny fraction of Copan’s business.)

“We love being free, eclectic and fast, knowing that we sometimes need to take calculated risks.”

That success has elevated Triva, who holds a 48% stake in Copan, into the billionaire ranks, worth an estimated $1.2 billion. Five other family members own the rest of the firm, which Forbes values at another $1.3 billion.

Copan’s runaway success has attracted the attention of several investment funds—Triva won’t name them—but the daughter of the company’s founder has no intention of selling. “We receive offers almost every day,” she admits. Confirms her nephew and Copan’s 32-year-old heir apparent, Giorgio Triva: “We’re at a size similar to other firms being sought out by these funds.”

But despite the SPAC boom and the proliferation of IPOs both at home and abroad—including the New York Stock Exchange listing in July of Stevanato Group, another Italian family-owned firm that received a Covid boost thanks to its vials for vaccines—she doesn’t plan to tap the public markets.

“When you’re a public company . . . it constrains your strategy and decision making,” she says. “We’re financially solid and independent, and this allows us to grow without seeking external funding.”

The growth of the past two years means Copan can continue expanding while keeping ownership firmly within the family. “We love being free, eclectic and fast, knowing that we sometimes need to take calculated risks,” Triva says.

That means investing in a future beyond the pandemic. In addition to medical tests, the firm also makes specialized swabs used in collecting forensic DNA from crime scenes. Clients run the gamut from Scotland Yard to the French Gendarmerie, which used Copan-made swabs to help identify the perpetrators of the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks. A microswab Copan and the Gendarmerie developed together enables authorities to analyze DNA from any bodily fluid—or even just fingerprints—in under two hours.

Beyond swabs, Copan already has a high-tech, and likely more lucrative, product to offer: a whole suite of machines and software that automates much of lab processing, from routine urine tests to complex bacterial infections. Lab automation, with $5 billion a year in revenue, is potentially a much bigger market than swabs.

“We’ve made some innovations in automation that have revolutionized microbiology,” Triva says, glancing over the vast warehouses and factories outside the window of her office.

Copan was founded in the northern Italian city of Mantua in 1979 by Triva’s father, Giorgio Triva. It initially distributed only lab products others made, such as test tubes. The company began making swabs in 1982, the same year Stefania’s older brother Daniele, a chemical engineer, joined the family firm as general manager.

Buoyed by strong product sales—including collection cups for blood analysis machines that gained a foothold in Japan—Copan expanded overseas, opening a subsidiary in California in 1995. Three years later it moved to its current location in Brescia, a major manufacturing hub.

Daniele Triva took over after his father’s death in 2000, and Copan’s fortunes changed forever when he pioneered the now-ubiquitous flocked swabs in 2003. While out shopping for a winter coat, Daniele noticed how the nylon fiber strips on clothes hangers stuck closely to the fabric, and he wondered if it could be replicated in swabs. A book about Copan written by Elisa Erriu and Mario Mazzoleni recounted a story where Triva supposedly challenged his technicians to design a swab with adhesive fibers that could act like a sponge and release more sample material than a regular Q-tip could—promising them free pizza if they succeeded. Copan maintains that the conception and invention of flocked swabs was done solely by Daniele Triva and that he actually “involved the rest of the team only for the industrialization optimization process of the product after patent filing.”

The new technology revolutionized diagnostics, making it easier to conduct routine tests for viruses and bacterial infections alike. “Before flocked swabs, they used aluminum wires to take nasal samples,” says Triva, grimacing.

Over the next decade, Copan expanded its California plant and opened an office in Shanghai. It began investing in automation in 2007, making proprietary machines called “walk-away specimen processors,” which robotically process thousands of samples a day, 24/7.

Starting in 2012, Copan became embroiled in a patent infringement battle with its largest competitor, Puritan Medical Products, after the American firm started producing its own flocked swabs. Copan alleges Puritan is violating several of its patents. The legal battle has raged for a decade and shows no signs of abating, with victories and defeats registered in courts from Maine to Germany and Sweden.

“They’ve always been our ‘illegal’ competitor,” Triva says. The ongoing lawsuit against Puritan in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maine was stayed in May 2020 to allow the two firms to focus full-time on making swabs during the pandemic; the litigation has since resumed. Puritan denies the allegations but declined to comment for this article.

A heartbreaking development occurred in 2014, when Daniele died at 54 after a seven-month battle with cancer. Stefania, who started working at the company right out of college and had been director of quality assurance and regulatory affairs, stepped up.

“It was a very tragic period . . . but I never thought about giving up,” she says, taking a moment to breathe. “The only doubt I had was about our ability to go on, because my brother was a very important leader. So I met with all our longtime employees and issued a call to arms. I told them, ‘We can only do this together.’ ”

Under her leadership, Copan hasn’t stopped moving. The company established a new engineering facility near its headquarters in 2016 and later opened new offices and factories in Japan, Australia and Puerto Rico. But nothing prepared Triva, or the company, for the virulent wave of Covid-19 that washed over Italy in early 2020. The first case in the country was diagnosed on February 20 in the small town of Codogno, about 50 miles southwest of Brescia—naturally, with a Copan-made flocked swab.

Facing a national emergency, Copan placed its employees on nonstop seven-day shifts to meet the Italian government’s demand for testing swabs. It also ramped up production to provide much-needed supplies to the United States, with U.S. Air Force planes landing in Brescia late that March and into April to pick up a total of 4 million swabs.

“Brescia was massacred by Covid-19, but our employees were always there,” Triva says, recalling a period when the city of 200,000 and the surrounding province were recording dozens of Covid-related deaths a day. “All you could hear was ambulance sirens, but they kept working, even on weekends and holidays.”

The company hired hundreds of new workers to keep up with the extraordinary surge in demand. It also received two grants for $10 million apiece in 2020, one from Apple’s Advanced Manufacturing Fund to build a new California plant, the other from the U.S. Department of Defense to increase production at its Puerto Rico factory.

It also doubled down on robotics, launching a machine called UniVerse that automates the preparation of samples for medical tests—for Covid-19 but also other infectious diseases including tuberculosis—freeing up overworked lab technicians to focus on less menial tasks.

Copan’s latest innovation is a machine that cuts diagnosis time by 80% for infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Built-in artificial intelligence helps keep the system running smoothly. Tests can be completed in roughly four hours, and negative samples are automatically sent to the trash.

Already the strategy seems to be working: Copan WASP, the firm’s automation division, recorded $54 million in revenue in the first nine months of 2021, up 39% over the previous year and exceeding its haul for all of 2020; it now makes up nearly a fifth of overall sales, the company says.

Triva credits her team, and her brother’s legacy, with that success: “[Daniele] sowed an entrepreneurial culture,” she says, “not just to me, but to the whole company.” And as long as she’s in charge, that tradition, and Copan itself, will remain all in the family.

Antigen Test Note: This story was updated on Feb. 8, 2022.